Soccer in Australia

a 136-year roller-coaster ride!

Semester 2 2011

Footscray

by Ian Syson

Recent developments in digitised newspaper archives have forever changed the way history is investigated. Simple term searches in the National Library of Australia's digital archive can now reveal in minutes articles and stories that would previously have taken months, or even years, of painstaking research to uncover.

One impact has been in the realm of sports history. Sport cultures based on founding myths and narratives of domination and permanence are starting to appear unstable. Sporting history's white lies and their more pernicious cousins are being exposed. My own field of research � the history of Australian soccer � is being drastically reshaped by archival discoveries.

The NLA database is searchable -- so we can discover evidence that was once nearly impossible to find. Previously, this data could only be found accidently or through an awful lot of hard slog using the old-fashioned techniques of trawling through microfilm and hard copy newspapers.

- Eg search "Brunswick Cricket Club" -> order earliest first. -> Nov 23 1857!

- Cumberland Arms

Already we can see the potential the database has in disrupting and correcting conventional narratives.

Without having to leave Melbourne, I have made a number of discoveries in the archive that question some of the established narratives of sport history in Australia .

Three general examples:

- From the Hobart Mercury in 1867 we learn of a group of Aboriginal footballers near Hamilton in Victoria .

- An 1880 regional news report in the Argus records the suppression of a Ladies' Football Club which had been proposed at Sandhurst .

- The Maitland Mercury reveals a form of football being played in Darwin in 1879.

In each example, factual evidence gleaned from displaced sources troubles established narratives.

Discoveries of this kind have led me to the conclusion that Every narrative, every story is wrong in some way . . . including my own.

Soccer history

A major suspicion I have confirmed over the past 3 years is that Soccer has a much deeper and broader Australian history than has been recorded by sports historians. The game is more �embedded' or domesticated than is usually assumed.

The archive reveals that soccer reports are there in newspapers but they are sometimes buried at the end of, or hidden within, a general football report. As is often the case footnotes are particularly revealing.

'Football' match listings, Argus 20 Aug 1910

Historians have overlooked vital pieces of information because of this. Also many have been guided by master-narratives that already structure and limit their narrative possibilities. (My own master narrative? Iconoclastic rather than hagiographic))

Consequently I've tried to adopt a sceptical and open-minded approach. Trust no established narrative; question all arguments about origins.

Three reasons:

- Established histories have been compiled with access to only a fraction of the available data and are necessarily limited.

- There are no origins only moments of confluence. Or, there are no fathers of the game (any game) � though there may be godfathers.

- Inscription is not origination. Because something is written down for the first time does not mean that it is the first time that it happened. The fetishistic emphasis on written rules and codes (of our own or someone else's) distorts the historical process.

The discovery.

Trying to find early examples of soccer in Australia, I had scoured the archive for references to football, soccer, british association football and had exhausted those searches.

Reading the articles had taught me aspects of the language used at the time and so I was able to make informed experiments with search terms. Making a search using the term �English association rules' I found reference to a game played between New Town fc and the Cricketers fc in Hobart on 7 June 1879 .

These clubs met for the return match on Marsh's ground, New Town, on Saturday afternoon, playing the English Association Rules. The result was a draw, no goals being kicked by either side.

Yet for many years Australian soccer had had an assumed origin point. Collective wisdom was that the first game was played in 1880 between the Wanderers and the King's School in Sydney. That game's originary status was undermined by the discovery of the 1879 Hobart game.

Recent suggests that even earlier games were played.

- 1878 a one-half soccer/one-half rugby game in Sydney

- 1876 the new Petrie Terrace club in Brisbane initially adopts London Association rules

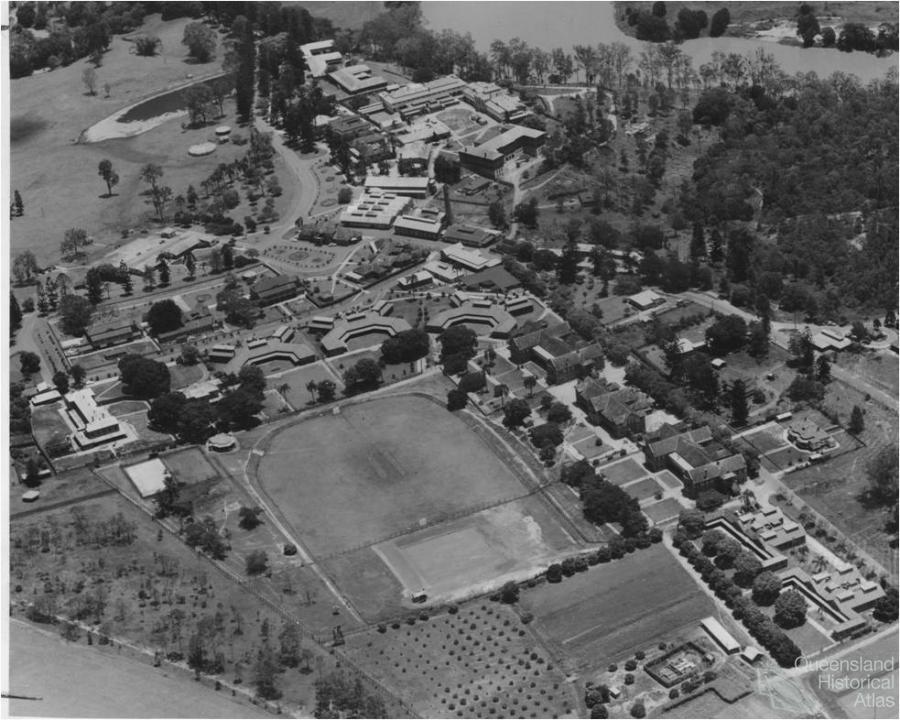

The latest in line for first-game-status was recently confirmed (in a footnote) as having occurred on Saturday 7 August 1875 in Woogaroo (now Goodna) just outside of Brisbane. The Queenslander of 14 August reported that the Brisbane Football Club met the inmates and warders of the Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum on the football field in the grounds of the Asylum:

. . . play commenced at half-past 2, after arranging the rules and appointing umpires; Mr. Sheehan acting as such for Brisbane, and Mr. Jack for Woogaroo. One rule provided that the ball should not be handled nor carried.

In itself this description is not enough to justify the claim that the game is soccer (or British Association Football as it was then known). The clinching evidence comes from the Victorian publication The Footballer in 1875 which notes in its section on �Football in Queensland' that the �match was played without handling the ball under any circumstances whatever (Association rules).� (p. 80)

Wolston Park Hospital Cricket Ground. Likely site of

the first recorded game of soccer in Australia

But this is still not the very first game of soccer in Australia. There is little doubt in my mind that there were earlier games. A rather tantalising history is suggested by the following list -- all discovered via the NLA database:

- 1873 a football association formed in Adelaide which initially adopts English association rules

- Throughout the early 1870s we see frequent advocacy of soccer in letters to the editor across the colonies.

- During the 1870s games were played in which carrying and handling the ball were outlawed in a number of places around Australia � Richmond in Tasmania. Can we describe these games as soccer? If not, how can we describe them?

- E. 1870s � recollections in the Mercury in the 1920s of soccer being played in the Hobart Domain.

- It is possible that the 1870 game in Melbourne between the Melbourne Football Club and the Police was played under British Association rules � though more research is needed to nail down this particular game.

- Letter to Bell's Life in 1867 advocating the adoption of soccer in Sydey.

A radical leap in the argument is involved in the speculation that when the Melbourne rules of football were laid down in 1858, 1859 or whenever, soccer was close at hand as an influence.

But soccer not codified until 1863? There is an argument to be made that a 'game resembling soccer' was certainly in existence in Australia well before the ostensible date of codification.

My article in Meanjin.

Indeed �a game resembling soccer' is a way to describe the very first example of the Melbourne Rules laid down in 1859, as �Free Kick' attests:

The [English] Football Association was accordingly formed, and set of rules drawn up, which by a very curious coincidence, are very nearly similar to those which were decided on at a meeting of representatives of football clubs, held at the Parade Hotel, near Melbourne, some 5 years ago � Whether a stray copy (for the rules were neatly printed and got up) ever found its way home I do not know, but if not it is a strong argument in favour of our own code, that the football parliaments assembled on opposite sides of the globe, should bring the identical same result of their labours. (�Free Kick', letter to Bell's Life in Victoria, 14 May 1864, p. 2.)

As far as �Free Kick' is concerned, the similarities between soccer and Australian football in 1864 were far more significant than the differences. Indeed, games resembling soccer have been played in Australia for as long as any other code of football.

There we have it: soccer was in the vicinity at the beginning of organised football in Australia. It has been a part of the sporting fabric of the whole nation ever since (historically widespread in ways that the AFL would envy). And it remains a significant part of our sporting landscape. Its ongoing struggle for legitimacy then is surely an object of bafflement.

Soccer's struggle for legitimacy

There is a fascinating story waiting to be told about why the Woogaroo Asylum played soccer when all other clubs around the region were playing rugby. As is often the case with code choice, it may well have boiled down to the preference of the Asylum's superintendent or even the players themselves. Superintendent Jaap was a Scottish educated doctor who may well have been a soccer advocate.

But the choice may also have been determined by assumptions about what would or would not be an appropriate game for inmates to play. This is a matter for conjecture and further research.

If it were the case the this game was in fact the very first one in Australia there would be an even more interesting story available in imagining that the guiding spirit of Australian soccer stems from its founding in a psychiatric hospital � a place of intense difference, alienation, separation, paranoia and insanity.

Soccer is indeed sick but metaphors of madness will not do. First, the employment of such metaphors would be to trivialise mental illness. Secondly, the game's ills have less dramatic (and more complicated) explanations.

As a game and an institution, Australian Soccer has manifold problems that have emerged and been repeated throughout its history. A truism of contemporary Australian sport discourse is that soccer enjoys high, if not the highest, participation rates of all sports. Yet it seems unable to translate these rates into mainstream sporting success.

This is not just a recent phenomenon. The Australian game has boomed a number of times:

- the 1880s,

- immediately prior to WWI,

- the 1920s,

- the 1950s and 1960s,

- the mid-2000s.

In each of these periods (save the latter), waves of migration brought new communities with a love of the game to either replenish it or establish new clubs and outposts. Migrant communities based around particular industries like coal mining, created strong soccer cultures in regions such as the Illawarra, the Hunter and Ipswich.

Andrew Reeves writes:

[By 1927] migrants had begun to imprint something of their culture and activities on the character of Wonthaggi. The town, for example, now boasted its own soccer league. Only on the Australian coalfields, it seems, could soccer rival rugby or Australian Rules Football at that time. In Wonthaggi, too, it remained a sport with appeal to specific groups, as the team names "Wonthaggi Thistles' and 'Caledonians' suggest. (Up From the Underworld, 49-50)

Paul Mavroudis is working on the literature of Australian soccer and has found a novel set in Cessnock in the 1940s which completely naturalises soccer, calling it football and having it as a 'normalised' aspect on community life.

I have written elsewhere about how South Hobart Football Club obtains a unique sense of permanence and belonging at its home ground in Washington St.

Even alongside other football cultures the game managed to flourish. Before World War I, for example, crowds of up to 6000 would sometimes flock to soccer matches on the Fitzroy Cricket Ground. In 1960s Melbourne, soccer crowds were starting to compare with footy crowds, producing some consternation in VFL circles. Massive crowds attended international and exhibition games across the country throughout the twentieth century.

There have been moments and places where soccer has been naturalised and local and even dominant.

Yet for all of the spikes of interest in the game, it has always receded into the background just when success seemed close at hand. War and Depression have been significant suppressing factors beyond the game's control.

The Depression of the 1890s obliterated soccer from the Victorian map while all of the subsequent gains made prior to World War I were wiped out by a near-unanimous display of loyalty from Empire-supporting soccer players.

The Depression of the 1930s again stifled a growing culture.

Soccer's capacity for self-destruction

Unfortunately, not all of soccer's ills can be attributed to historical accident. Matters within the game's control have not always been impeccably handled. Decisions made by those in power have run from the silly to the mind-bogglingly stupid to the apparently suicidal.

Too often, Australian soccer has been run either by the self-interested, the amateur or the incompetent � sometimes by all three at once. Though usually all three are competing for control of the game at any stage of its history we care to look at.

Today we see the stunningly rich and mildly famous buying clubs and holding the spectators and the game to ransom through decisions unfathomable to ordinary punters.

People without ambition for the game or with more care for their own factional or business interests jostle for space with the clearly foolish and the careless who don't understand and probably don't even like the game and culture over which they have stewardship. Club ambition has often over-ridden the best interests of the game. Soccer has had its legions of good and honest toilers but they have been swamped by the power, corruption and dominance of the few.

Soccer as victim?

A great debate exists within the Australian soccer community as to whether the game's ills are a matter of internal incompetence or external pressures. I tend to take the view that had soccer been run ethically by competent individuals then the pressures from outside would not have mattered. However, given the internal incompetence, outside pressures have left their mark.

The game has been subject to resistance from other codes of football and xenophobic communities and agencies that have engineered opposition to its growth. Johnny Warren famously encapsulated the sense of emnity in the title of his autobiography, Sheilas, Wogs and Poofters . He argued that soccer was seen as a foreign game, not one for �real' Australian men. While the latter prejudice is breaking down, soccer continues to be constructed as a foreign game � despite its more than 136-year history in Australia.

This supposed foreignness has been used to justify the game's exclusion. And the refusal of access to grounds has been a major stumbling block for the game � one that still plays out in Victoria where it is claimed that there are more children wanting to play the game than there are grounds made available for them to play on.

Moreover, a rhetoric of fear has developed across Australian culture, embodied in newspaper headlines from the middle of the twentieth century such as, �Soccer Threat Grows�, �Soccer Menace� or �Soccer Wants Your Boy�.

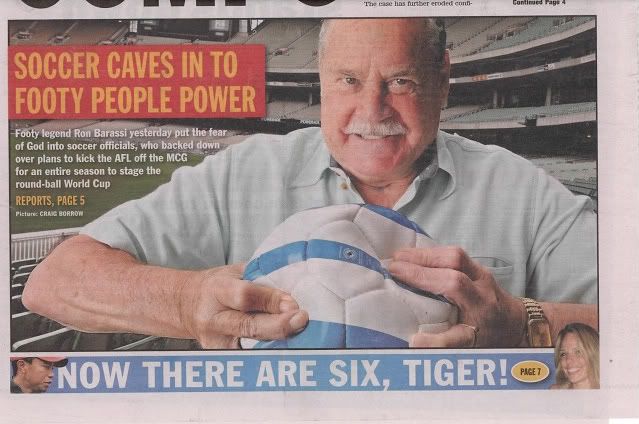

This rhetoric today is articulated via the media's expression of fear of soccer crowds and their supposed tendencies to engage in violent behaviour. During the World Cup bidding processes a moral panic was created by those who argued that our hosting of the Cup would threaten our �domestic' games.

Ron Barassi

So for all of soccer's internal flaws and mistakes we need to remember that like all systems this one too has a broader context. Soccer's incompetence and mitigating histories have not occurred in a vacuum.

Nonetheless, the game seems caught up in a seemingly interminable loop of peak and trough, success and failure. Five years ago we experienced what appeared to some to be the final awakening of the sleeping giant via World Cup qualification and our credible performance in Germany. The newly formed A League received a real boost from the World Cup and its attendances were initially impressive. The Crawford Report appeared to have helped engineer vital structural reforms in the game's administration.

In recent times the mood has once again swung. Average crowd numbers are waning. The FFA is a laughing stock over the failed World Cup bid. It is still ludicrously expensive for kids to play soccer. And sometimes there seems little prospect of good governance for the game.

Karl Marx said, � History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce.� What would he have made of Australian soccer as it repeats its errors and failures decade after decade after decade?

The recent signings of Harry Kewell and Brett Emerton have created another wave of optimism that might well usher in a new upswing or might simply be a temporary papering over the cracks.

Yet there is some hope amid all of this pessimism. Leading soccer historian, Roy Hay has made the point that the recent soccer boom is the first one not fuelled by migration. Many of the millions watching Australia's World Cup performances, the hundreds of thousands playing the game were locally born � as are many of the tens of thousands attending A League games.

Almost unnoticed, and despite resistance, the game appears to have achieved its long-desired goal of domestication.

Another point is that as sport becomes more oriented around business models and solutions, old-fashioned resistances based on cultures of masculinity and domesticity are being replaced by hard-headed profit and loss sentiments. If soccer can make someone money, it will be allowed to do so.

Finally the one gloriously shining light in all of this murky history it is the fact that the game, despite all of its setbacks and stupidities, really is a beautiful one whose qualities will rescue it from whatever despair into which it falls. And whenever soccer falls in Australia it falls into the large safety net of a massive participation base. For too long, those charged with running the game have taken these facts for granted. Is it too much to hope then that the game will soon be run by those who would cherish and nurture them?

Articles by Ian Syson

- Shadow of a Game: Locating Soccer in Australian Cultural Life Meanjin

- The Genesis of Soccer in Australia, The Conversation

- powerpoint

- Bonita Mersiades, 'Championing the Game' Age 14 September 2011

Questions to Consider

1. Why is soccer not Australia’s main football code?

2. What are some of the aspects of its development that have undermined soccer in Australia?