ACL 1002

Studying Poetry and Poetics

Semester 2 2012

Footscray Park

Lecture 3

Poetry and Communication

Ian Syson

This apparently innocent and simple question is one bound to cause controversy among poetry circles and beyond.

Over 50 years ago William J Rooney said:

- In the last seventy-five years the problem of poetry and communication has been the most insistent theme of most criticism

- the flow of opinion . . . has emphasized . . . the non-communicative aspects of poetry

Still a fairly dominant position. One closely related to the critical school of New Criticism.

The contemporary poetry editors of most literary magazines in Australia would hold a position similar to this one.

I like to examine this question by looking at a poem by the English Romantic poet John Keats. His 'Ode on a Grecian Urn' is one of the centrally important poems for a number of critics. It embodies the kind of poetic values that they were trying to elevate.

Cleanth Brooks Well-Wrought Urn uses the poem as its centrepiece.

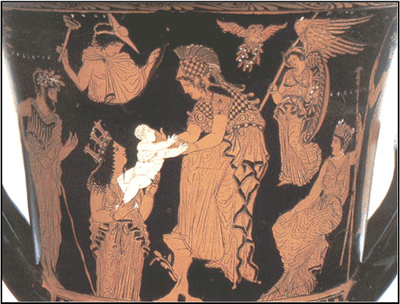

Some Grecian urns

Keats' ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn'Thou still unravished bride of quietness,

Thou foster child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loath?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endeared,

Pipe to the spirit dities of no tone.

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal—yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss

Forever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed

Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu;

And, happy melodist, unweari-ed,

Forever piping songs forever new;

More happy love! more happy, happy love!

Forever warm and still to be enjoyed,

Forever panting, and forever young;

All breathing human passion far above,

That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloyed,

A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest,

Lead'st thou that heifer lowing at the skies,

And all her silken flanks with garlands dressed?

What little town by river or sea shore,

Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel,

Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn?

And, little town, thy streets for evermore

Will silent be; and not a soul to tell

Why thou art desolate, can e'er return.

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity. Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say'st,

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty"—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

Keats' poem can be read as expressing an aesthetic that keeps the literary object apart from context, influence and indeed communication. If indeed it communicates it does so at anything but a literal level – or even on the level of meaning.

Pipe to the spirit dities of no tone.

There are of course other opinions – that poetry is primarily about communication between people and that without communication it fails as an art form.

Cleanth Brooks in The Well-Wrought Urn puts it another way

I think our initial question, 'What does the poem communicate?' is badly asked. It is not that the poem communicates nothing. Precisely the contrary. The poem communicates so much and communicates it so richly and with such delicate qualifications that the thing communicated is mauled and distorted if we attempt to convey it by any vehicle less subtle that that of the poem itself. (pp. 72-73)

Rather typical of the New Critic school. The 'heresy of paraphrase'.

See here for Jack Stillinger's discussion of the ways in which Keats' poem has been read, taught and valued by succeeding generations.

TS Eliot felt that "Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood."

Whereas other ways of thinking might suggest that something needs to be understood before it communicates.

2. If so what does poetry communicate?

Look at some songs

A-Wop-bop-a-loo-lop a-lop-bam-boo

from 'Tutti Frutti' performed by Little RichardI am the Walrus Lennon and Macartney

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0yNcE8c3j2M

Blake's 'The Tyger'

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?In what distant deeps or skies,

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare sieze the fire?And what shoulder & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand?& what dread feet?What the hammer? What the chain?

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? What dread grasp

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the lamb make thee?Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

Poetry communicates:

Substance

Form via –

Rhythm

Sound

Words

Meaning

3. At what levels does it communicate meaning?

- Literal

- Metaphorical

Greek ‘Carrying from one place to another; transfer'. A trolley in Greek airports is still called a metaphor

- Tenor, vehicle, ground (I.A. Richards)

- Dormant metaphors

- look at definitions

Taken from http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/hopkins/hopkins13.html

Sprung Rhythm is Gerard Manley Hopkins' term for a complex and very technically involved system of metrics which he derived partly from his knowledge of Welsh poetry. It is opposed specifically to "running" or "common" rhythm, and provides for feet of lengths varying from one syllable to four, with either "rising" or "falling" rhythm.

From our late twentieth-century perspective, it may seem like Hopkins was re-inventing the wheel: almost none of what he argued for was actually new in English poetry; Tennyson , Morris , and Swinburne had all experimented with Old English meter very like the Welsh verse which Hopkins had learned; and no other poet has since used sprung rhythm regularly. But as with "inscape," sprung rhythm is the theoretical expression of a concern which had obssessed every nineteenth-century poet. Also characteristic of Hopkins was his need to back up his poetic practice by a theory which demonstrated the immanence of God in his poems.

'That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the comfort of the Resurrection' By Gerard Manley Hopkins

Tomcat

James K Baxter

This tomcat cuts across the

zones of the respectable

through fences, walls, following

other routes, his own. I see

the sad whiskered skull-mouth fall

wide, complainingly, askingto be picked up and fed, when

I thump up the steps through bush

at 4pm. He has no

dignity, thank God! has grown

older, scruffier, the ash-

black coat sporting one or twoflowers like round stars, badges

of bouts and fights. The snake head

is seamed on top with rough scars:

old Samurai! He lodges

in cellars, and the tight furred

scrotum drives him into warsAs if mad, yet tumbling on

the rug looks female, Turkish-

Trousered. His bagpipe shriek at

Sluggish dawn dragged me out in

Pyjamas to comb the bush

(he being under the vetfor septic bites): the old fool

stood, body hard as a board,

heart thudding, hair on end, at

the house corner, terrible,

yelling at something. They said

'Get him doctored.' I think not.

Ann Sexton, ‘Woman with Girdle' + sound files

.